Underreporting Fume Events: Perception Trap and Safety in Aviation

The terminology

Some people speak of the "tip of an iceberg", others call it "underrecorded", in science it is called "underreporting" - when information or statistics do not reflect what they actually should or should not. In such cases, one knows that such data are not useful because they are incomplete and not representative.

One could (if one wanted to) take this as an opportunity to ensure that in future such figures become more meaningful by (more or less) capturing what they are supposed to.

This is also the case with "fume events", which should more correctly be called "cabin air contamination events" because (smoke) fumes are only rarely seen in such incidents. Nevertheless, we will stick to this term because it has become established. Still, we will also use the more appropriate word, e.g. when we speak or write about potentially contaminated cabin air.

We will continue to use the term "underreporting" for the statistical problem of incompleteness. This expression - in contrast to the two formulations mentioned above - emphasises more clearly that the incomplete figures have a genuine reason: namely that they are - actively or consciously - only incompletely recorded or reported. The incompleteness, therefore, has real causes, which we will discuss later - after we have presented the problem and its consequences.

"Underreporting": the statistical problem

We do not have exact figures. Nobody has them. Probably not even the airlines. They are the least interested in this data, although they should have it because the statistical problem is potentially becoming a safety problem; more on that later.

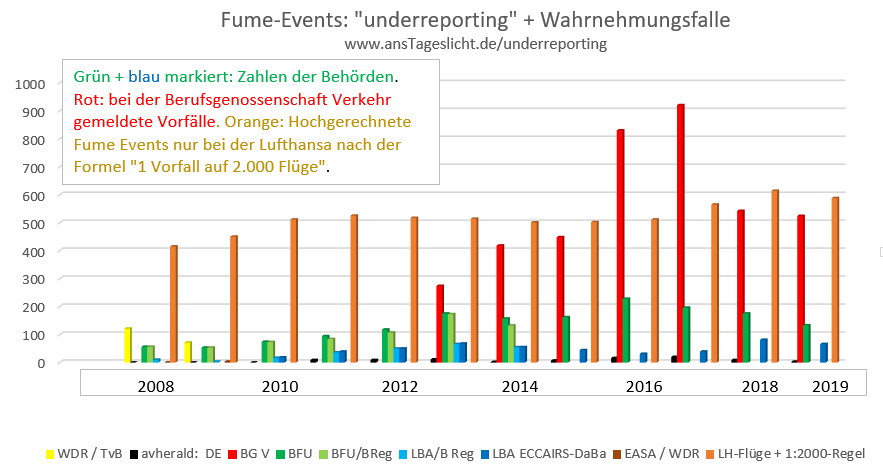

The underreporting problem is illustrated by various figures, which we compile here:

Data

- from the three responsible authorities:

- the Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation - BFU (in green)

- the Federal Aviation Authority - LBA (blue) a

- the European Aviation Safety Agency EASA

- Reports of fume event occurrences that crew members pass on to the responsible Berufsgenossenschaft Verkehr (BG V), e.g. if they want to report an "accident" (occupational accident) (in red)

- extrapolated fume events at Deutsche Lufthansa, according to the formula "1 fume event per 2,000 flights". This empirical value is based on an evaluation and publication of the British "Committee on TOXICITY" from 2007. If one converts the 1,177,315 LH flights, this results in 588 fume event incidents.

The discrepancy of underreporting of fume events in Germany in 2019 is, therefore:

588 (Lufthansa only: orange) – 524 (BG V: red) – 133 (BFU: green) – 66 (LBA: blue):

If the numbers of Condor and TUIfly flights are included in this British experiencial formula, figure 588 increases by ca. 10% to 646. Other airlines such as easyJet or Ryanair, which also land and take-off from and at German airports and in some cases employ German staff, are not included.

Regardless of which peak value is assumed: The statistical range reveals a (very) large difference. To put it bluntly: the German aviation supervisory authority LBA only receives 10% of such incidents, if extrapolated figures are taken as a basis. So much for the validity of official statistics.

The graph "Fume Events: Underreporting + Whistleblowing" is updated annually as part of the research project "Risk Perception" (DE). In future, it will serve as a seismometer to quantitatively measure underreporting.

It can be downloaded here in different formats: as a PDF with the corresponding figures and sources, as a tif graphic in high resolution, and as a simple png.

The statistics are declared differently: There are 66 reports recorded at the LBA listed as "incidents involving oil odour", the BFU counts "incidents involving smoke and odour", for 2019 a total of (only) 133, twice that number. Or, to put it another way: of what the BFU counts, only half is officially recorded by the Federal Office of Civil Aviation (LBA), which is subordinate to the Federal Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure.

How systematically inconsistent the official figures are, we explain here Underreporting: further explanations (not online yet) - for statistical gourmets.

"Underreporting": the perception trap

It is well known in communication science that one's perception and/or that of public perception can consist of "distorted perception" - when so-called perception filters are used - consciously or unconsciously.

Such perception filters can consist of a) ignorance, b) ideological filters (e.g. prejudices) and c) consciously looking away or not wanting to perceive.

The media play an eminently important role here both for individual and public perception, i.e. for the question of whether and to what extent the public (general, professional, political) succumb to such filtered information. They decide - depending on the value of their self-defined news factors and their journalistic concept ("corporate philosophy"). They determine what people or their users get to read, see or hear. And what they then know. Or what they think they know, which applies equally to social media.

Missing information, half-information or misinformation regularly end in distorted perception. Or lead directly into a perception trap. Distorted perception always means a "trap" when it results in a discrepancy between what one thinks one knows and what is; this becomes relevant when this trap can be a matter of life and death, which brings us to the connection problem of the perception trap in fume events: the safety problem.

Underreporting and safety in flying: a safety paradox

Flying is known to be one of the safest modes of transport; figures show: 1.35 million people died in road traffic accidents worldwide in 2019. Aircraft disasters killed 240 people (2018: 523). If one converts the number of deaths to the distance travelled - for the sake of better comparability - one arrives at the same result: for every 1 billion kilometres travelled, there are 0.003 deaths in the case of aeroplanes. For cars, it is 2.9, for bicycles 30, i.e. considerably more, and for motorbikes as many as 53. If you take the railway, travelling by train (0.03) is a little more dangerous than flying. Ships come away best: 0.00001 deaths per 1 billion kilometres travelled. They were calculated by Flüge.de.

The fact that flying comes off so well has to do with the principle of 'learning from mistakes' or 'share your experience'. Over decades, countless pilots and others have pointed out weaknesses, and the aviation industry and regulatory authorities have (at least mostly) reacted. We reconstructed it in another context in the chapter "Reporting systems in aviation - whistleblowers also indispensable." (directly accessible at www.ansTageslicht.de/Meldesysteme - in DE only).

But this does not always work. Two examples.

Case study Boeing 737 Max 8:

One of the latest cases of non-action concerns the issue of the "Boeing 737 Max 8", when the authorities only took action after two aircraft of this type had crashed one after the other. Here, too, there was "underreporting": several pilots had wondered about the strange behaviour of this type of aircraft in particular situations - the manufacturer Boeing had not told them about the changed aerodynamics and the new software that was supposed to compensate for this: no "reporting".

The pilots, in turn, had sporadically shared their experiences with this 'new' aircraft with their airline, but not with all the other Max 8 pilots. Therefore, nobody had all the relevant information that would have been important: not the manufacturer Boeing, not the airlines, not the regulatory authority, nor the pilots.

The communication of such information was, as it later turned out in an air accident investigation, also undesirable.

Communicating all the innovations of this changed aircraft type and its unique features would, for example, have caused the airlines additional costs for training the pilots. Cost savings, therefore, took precedence over safety. Result: 2 crashes with 346 fatalities. Pilots and crew included.

Case study Germanwings flight / Airbus 319-132:

The problem of "fume events" is similar. We have documented how such "cabin air contamination events" can occur under What is different when flying at an altitude of 10 km?

What the immediate consequences can be when both pilots in the cockpit are simultaneously virtually incapacitated, when the pilots "lose their senses" from one second to the next, when the "field of vision is suddenly restricted", when a pilot is "afraid of losing control over his own body and actions", when it becomes "difficult to concentrate at all" in order to "get the shitty plane on the runway", we have illustrated with several flight reports from the cockpit, which pilots have subsequently written down.

The original quotes quoted above come from an incident on 19th December 2010, when - thank goodness - everything went well in the end. But - as the co-pilot wrote: "I can't imagine what would have happened if we had passed out! The plane would have followed the LOC and GS and hit the threshold in Cologne with 8 tons of residual fuel - because of snow - and 144 guests + 5 crew members. I don't want to imagine the catastrophe to this day."

The (subsequent) flight reports from which these short quotations originate can be found at www.ansTageslicht.de/Cockpit-Flight-Report. The event of this flight (Vienna - Cologne/Bonn) is reconstructed at www.ansTageslicht.de/casestudy-Germanwings .

Systematic underreporting of such incidents plays down the dangers. In real terms, "underreporting" poses a risk to aviation safety - with all the possible consequences that entails.

Underreporting of fume events is a paradox in an industry that thrives on the label and image of "aviation safety".

The situation of interest and motivation in fume events

Strictly speaking, the principle of tapping the fresh air needed for the cabin and cockpit at an altitude of 10 kilometres via the engines ("bleed air") is a design flaw. Changing this would mean that around 23,000 jet aircraft worldwide would have to be converted—a cost factor.

To thoroughly 'clean' an aircraft after a fume event would mean replacing the ducts (air pipe connections between the engine, pre-cooler and air conditioning system), as well as the entire air conditioning distribution system. An aircraft would have to stay on the ground for up to 30 hours—a cost factor.

The pilots, for example, know that. They also know that their employer is "not amused" if a captain enters such a report in the documentation provided for this purpose (e.g. TechLog, FlightLog) and/or forwards a report to his airline or the BFU or other institutions.

Another problem is that there are no standardised reporting channels. And certainly no mandatory "Incident Reporting Systems". Internally, the airlines only provide information in the form of 'recommendations'. To the outside world, however, there are constant announcements to customers and politicians that "safety comes first".

Underreporting: Health risk for the crew

Underreporting as a risk to the safety of flying is one thing. The health risk for the crew is another.

In the case of the Germanwings flight at Cologne/Bonn airport in December 2010 outlined above, not only did the landing end smoothly, but the two pilots were also lucky as far as their health consequences were concerned. The captain was able to resume his duties after four days; the co-pilot was unable to fly for a whole six months for medical reasons (more at www.ansTageslicht.de/casestudy-Germanwings).

People react differently to toxic effects, depending on their genetic disposition ("genetic polymorphisms"). Reactions in the human body can occur acutely, as was the case with the Germanwings flight in question. The more common variant consists of additional long-term health damage, which is often also beyond repair.

For the crew, the aircraft is their workplace. Toxic effects occur a) as permanent background exposure and b) in real cases in increased, in the worst case: massive doses.

We have documented the health effects of those affected by fume events using the fates of 3 (former) flight attendants and 3 (former) pilots as examples at www.ansTageslicht.de/Betroffene-Fume-Event (DE).

Underreporting: Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation (BFU)

When the Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation (BFU) conducts investigations, it is not - according to its mandate - about the question of guilt and certainly not about apportioning blame. It is solely about reconstructing an "accident" and finding answers to the two questions a) how could this happen and b) what can be learned from it to prevent such things from happening in the future?

This mission is entirely in the spirit and tradition of the principle that has made flying one of the safest means of transport: Learning from mistakes by 'sharing your experience'. So far, so good.

However, one has to take a closer look at a) what exactly happens at the BFUand b) when.

The BFU distinguishes and takes action in the following cases:

- "accident",

- "serious incident"

- "serious and fatal injuries".

Accident:

An accident is only considered to be one when someone has been seriously or fatally injured, or the aircraft has suffered damage or is missing. Then the BFU must "investigate".

Serious incident:

In addition to the "accident" category, there is the "incident" case, which is an "occurrence other than an accident" but which is "related to the operation of an aircraft and affects or could affect its safe operation." One could declare these cases as what one could also call "incident" (as opposed to "accident").

In this context, the BFU only takes action if there is a "serious incident". Meaning: incidents "the circumstances of which indicate that an accident almost occurred."

"Almost" therefore means: If someone could have been "seriously" or "fatally" injured.

For this purpose, the BFU lists some exemplary cases, the "list of which, however, is not exhaustive" and is only intended "as a guideline for the definition". These include the following situations, among others, which may be of significance in the case of fume events:

- when pilots (have to) reach for the oxygen mask

- a crew member becomes incapacitated during the flight.

This was the case with the outlined Germanwings flight Cologne/Bonn: the pilots had reached for the oxygen mask and also more or less lost their ability to act shortly before the touch-down. However, the BFU did not start investigations until this incident came up nine months later in the context of an expert hearing in the Tourism Committee of the German Bundestag (more www.ansTageslicht.de/casestudy-Germanwings).

An isolated case? What if, for example, pilots become incapacitated so quickly that they do not (or can no longer) reach for the oxygen mask or do not consider this an option in their limited perception? For example, because they were not previously alerted by an intense smell of "wet socks" or "wet dog"?

"Incidents" of this kind are according to BFUs understanding and its function, not a reason to initiate investigations - regardless of whether an event of "smoke or odour development" was reported at all.

Serious injury:

This leaves the last case in which the BFU must initiate investigations: "serious injuries", which are defined as such, among other things, if - concerning fume events - the following occurs and those affected have to

- spend at least 48 hours in a hospital in the immediately following days.

- „damage was caused to internal organs".

What happens if the affected person goes to hospital after landing and the doctors there (e.g. also so-called D-doctors) do not arrange for admission - e.g. because they are unaware of the complexity of the illness or damage? What if damage to internal organs only becomes apparent after a latency period? What if the causal connection (in "full evidence") can no longer be established? What if the BFU, for example, delegates medical examinations to the Aeromedical Institute of the German Armed Forces in Fürstenfeldbruck and does not allow the person concerned to see the results of their investigation (as happened in the case of the co-pilot of the Germanwings plane)?

Underreporting by the BFU?

The statistical difference between the fume incidents extrapolated with the experience formula of the British Committee on TOXICITY (2019: 588 only at Lufthansa) and those reports received by the BFU (2019: 133) is considerable. Investigations are only initiated in exceptional cases. Thus, there is - intentionally or not - a twofold underreporting:

On the one hand, the BFU statistics are of little use in approximating and communicating the problem. On the other hand, the omission of potential risks in the context of the aeronautical safety principle of "learning from mistakes" represents an underreporting that is inconsistent with this.

Although the BFU addressed the issue in 2014 as part of a "Study on reported incidents in connection with the quality of cabin air in commercial aircraft" (in DE only), it only referred to the fact that it had "only limited possibilities" in terms of clarification (p. 87).

Other activities to make the topic a public issue have not been discernible since then.

Thus, this authority does not represent a driving force to lead politics and/or the public out of the perception trap. Instead, it prefers to make itself comfortable and refer to the large number of relevant paragraphs.

In response to our detailed questions, e.g. who decides,

- what "damage to internal organs" is

- and whether such damage is considered "serious injury" if, for example, it turns out to be irreparable,

the BFU answers flatly:

"For the Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation (BFU), the legal regulations of the EU Regulation on investigation and prevention of civil aviation accidents and incidents (Regulation (EU) No. 996/2010), the Aircraft Accident Investigation Act (FlUUG), as well as ICAO Annex 13 are relevant for its activities and thus also for the classification of events. These regulations apply to all events. The relevant definitions can be found in Article 2 No. 1 lit.a), 4, 7, 16 and 17 VO (EU) No. 996/2010 or §2 FlUUG."

Underreporting: a security risk also for air passengers?

For passengers, an aircraft is usually or in real (individual) cases a temporarily used means of transport. A fume event incident, even if it is massive, is usually 'dealt with', without significant health complications. This is because the vast majority of people do not know anything about it. If someone experiences any unusual symptoms after a flight, there is a (huge) probability that those affected do not associate this with a flight (e.g. on holiday).

The situation is different for frequent flyers. In the Netherlands, Aviation Medical Consult (AMC) conducted a survey in 2017 among 100,000 people, including frequent flyers: 500 people who had flown at least six times in the last 12 months.

From the survey results, the presumed phenomenon is that not only flight personnel are at risk, but also all those who (have to) regularly use the airplane as a means of transport for professional reasons.

While it can be assumed that frequent flyers know more about the problem due to more severe symptoms, this is not true for the broad mass of the occasionally flying population.

Underreporting, perception trap and safety risks

As a result, systematic, because institutionally conditioned underreporting means that the perception trap takes effect: the dangers to safety in air traffic and to life and limb, especially for the crew, are underestimated - systematically, because institutionally conditioned: in the public and among political decision-makers.

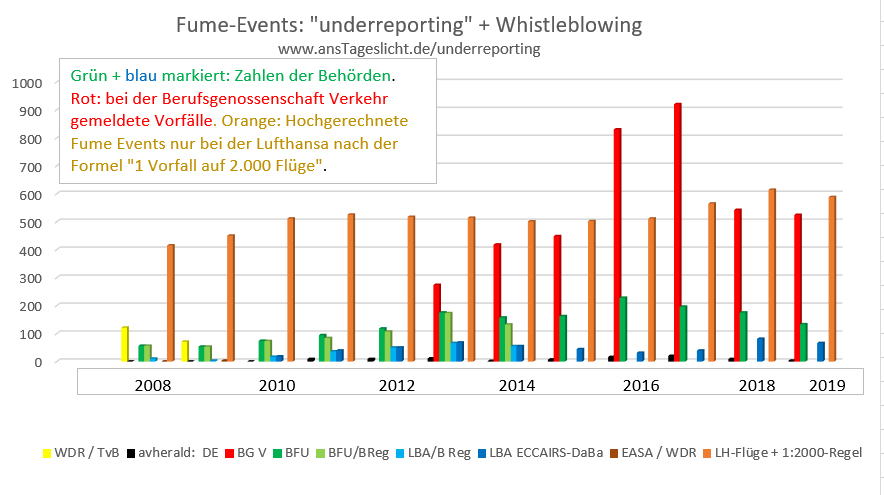

To change this, whistleblowers and informants are needed. The above graphic "Underreporting and perception trap" can be interpreted equally as "underreporting" and necessary "whistleblowing":

Remark

The likelihood that anything will change in this malaise, if underreporting and its related consequences are considered a grievance, is low.

Changes can not be expected on the part of politics or its executive authorities. Both levels are too interwoven with the aviation industry for that. The aviation industry is also not interested.

Similarly, the area of statutory accident insurance and its 'affiliated' occupational medicine sector is out of the question: the foreseeable cost burdens would be too significant (more at www.ansTageslicht.de/krankdurcharbeit).

So in the end, the only thing that can usually initiate change is a broad discussion and public pressure. And "whistleblowing", by passing on relevant information to those who give tips known in the public interest. Please find out more at www.whistleblowerinfo.de, on the Whistleblower Network pages, or also at How to communicate safely with us.

We have compiled what you can do in individual cases if you have been caught in a fume event and what the options for action are in general at What Can You Do!

This Site you are just reading is directly accessable at www.ansTageslicht.de/perception-trap-underreporting.

(JL; translation: BB)

Online am: 17.12.2020

Aktualisiert am: 06.01.2021

Inhalt:

The Fume Event Files: Players, Institutions and other Topics

- Regulatory Authorities and Air Safety - the case of the Boeing 737 Max 8

- Cockpit Flight Reports after fume event

- The hunt for Tricresylphosphate (TCP)

- Criticism of the SCHINDLER Study 2013

- Underreporting Fume Events: Perception Trap and Safety in Aviation

Tags: